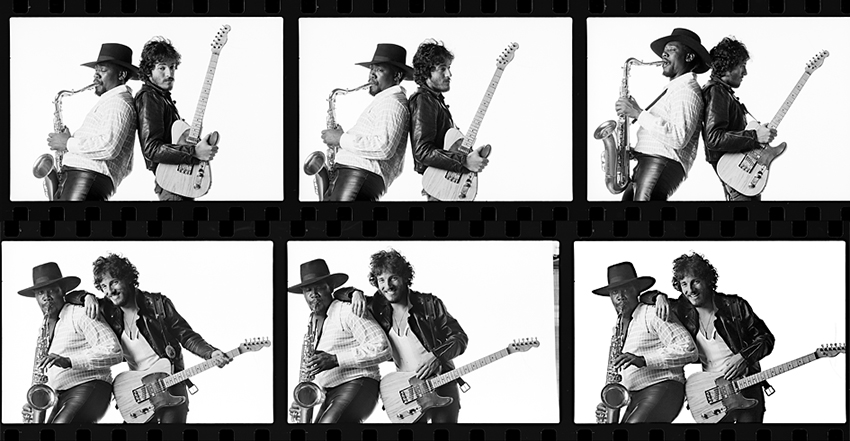

Eric Meola made one of the most iconic photographs in the history of rock ‘n’ roll: the cover photograph on Bruce Springsteen’s landmark 1975 album Born to Run.

Eric Meola is a highly regarded American photographer who is probably best known for his vibrant color images. His photographs are in many private and public collections including the International Center of Photography, the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC and the George Eastman House.

Without doubt the most popular photographs that we offer for sale at the gallery are from the Bruce Springsteen archives of Eric Meola. We hosted the world premiere exhibition of photographs from Eric’s Born To Run sessions at the gallery in 2006, and subsequently Eric has released other images from his Springsteen archives, including a range of beautiful portraits from his sessions in 1977/78 for Darkness on the Edge of Town.

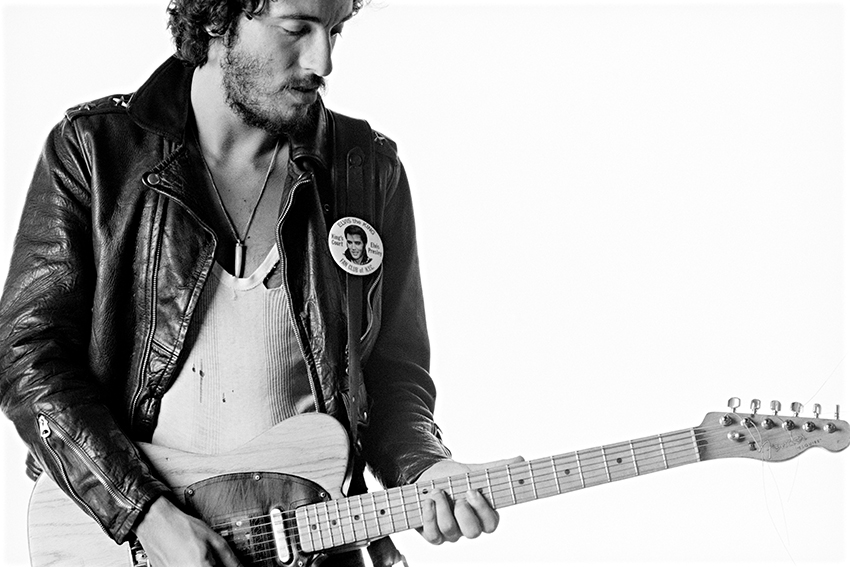

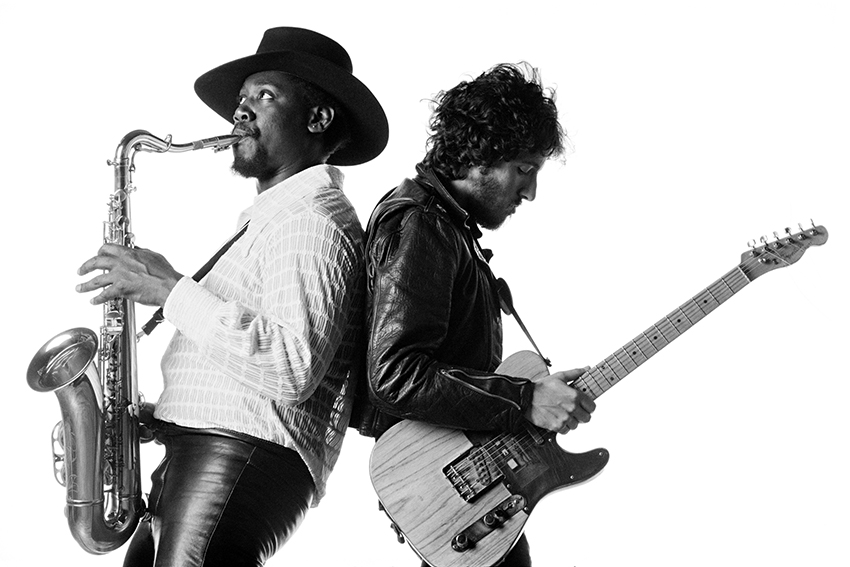

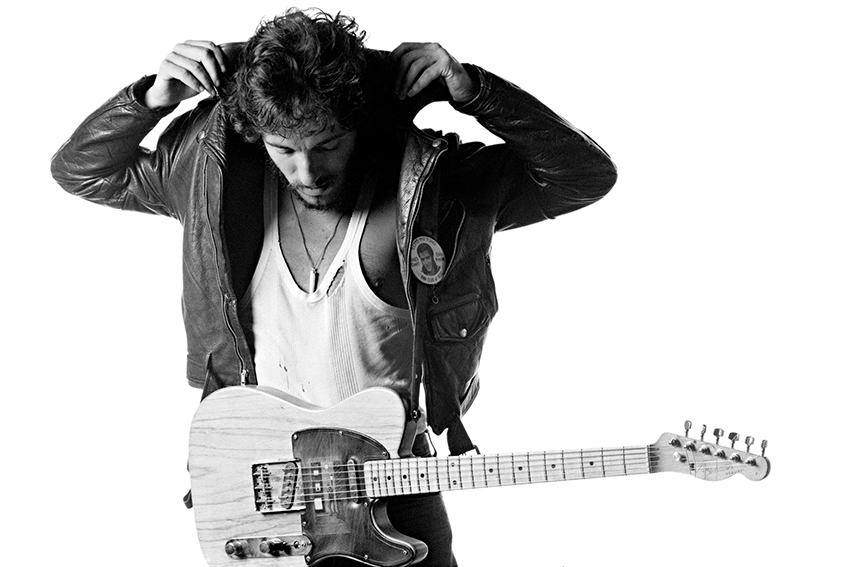

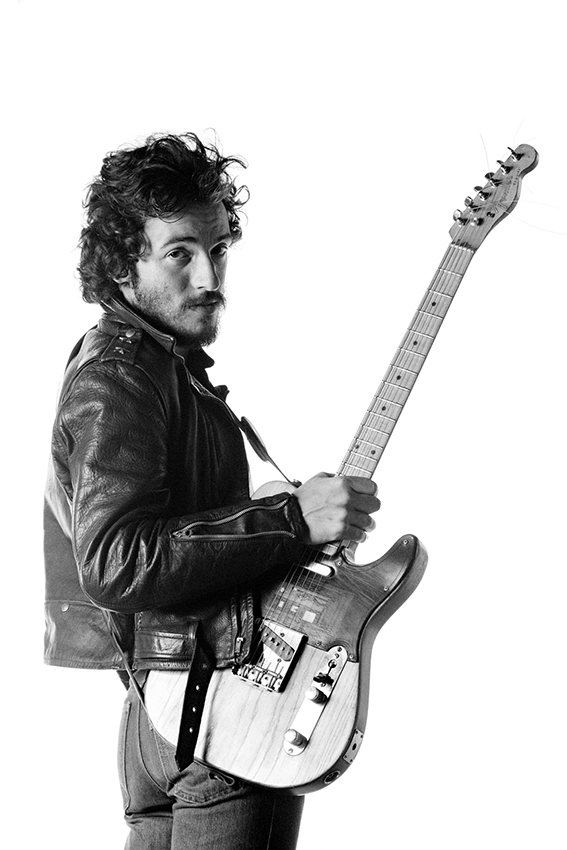

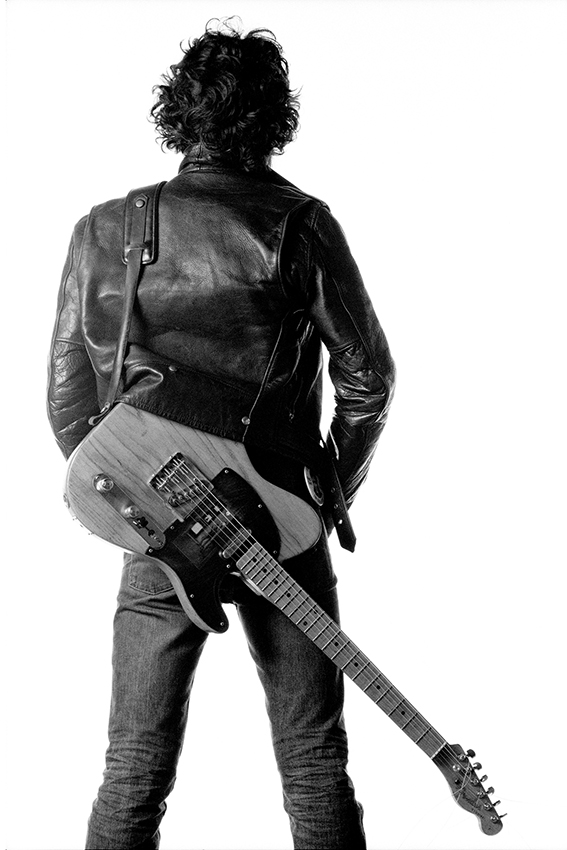

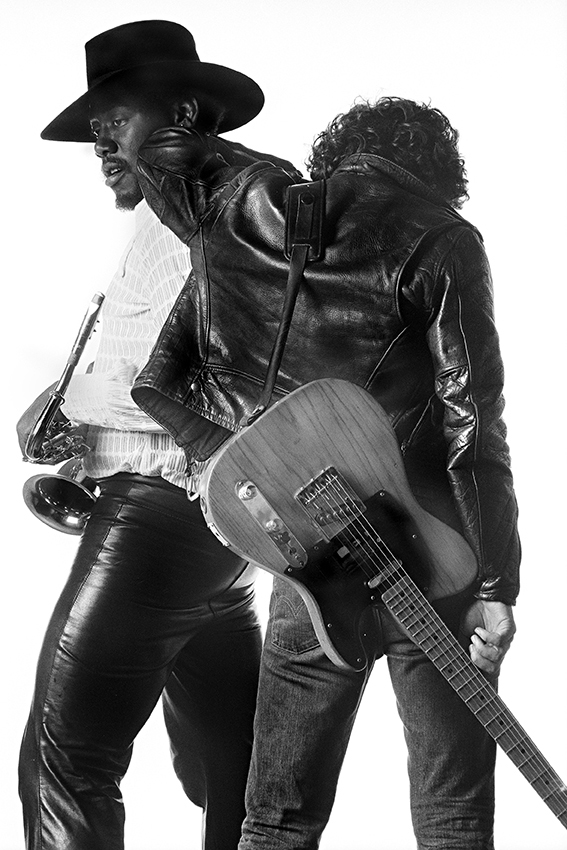

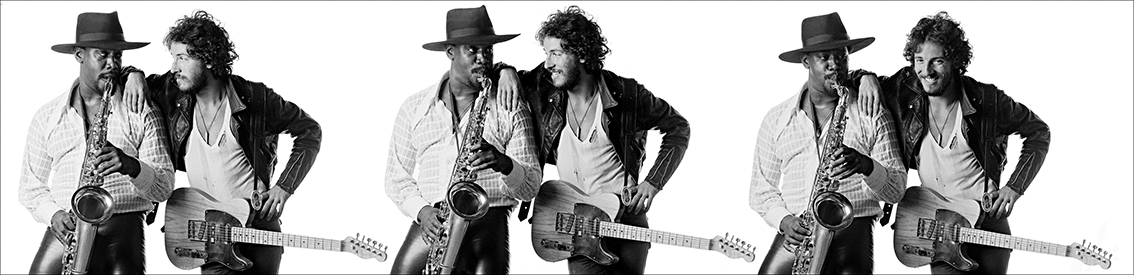

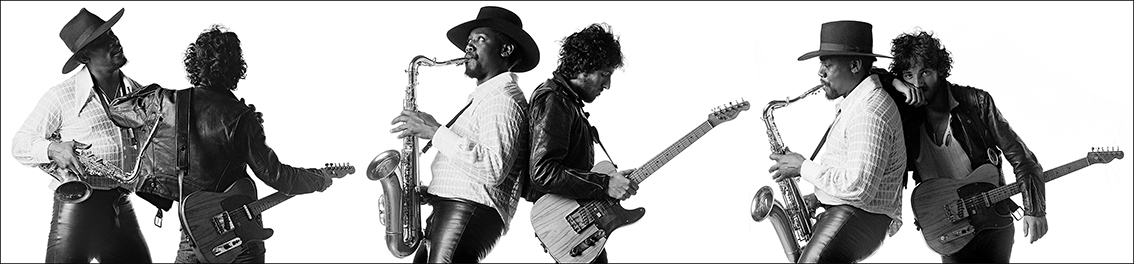

In stark contrast to the bulk of his work, Eric’s session with Bruce Springsteen and Clarence Clemons in 1975 to make the cover photograph for Born To Run (one of his few rock ‘n’ roll sessions) was shot entirely on black and white film.

The reaction from collectors to the quality of Eric’s prints – which are made by Eric personally – ranges from ” WOW” to ” Holy S**t these are amazing!” and everything in between.

Eric offers his work to collectors in a choice of physical size options, in very small and exclusive limited editions.

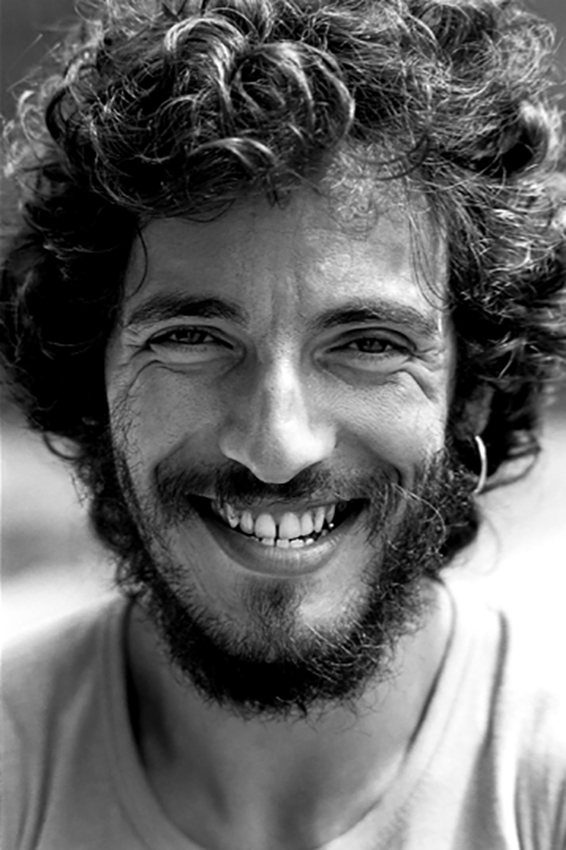

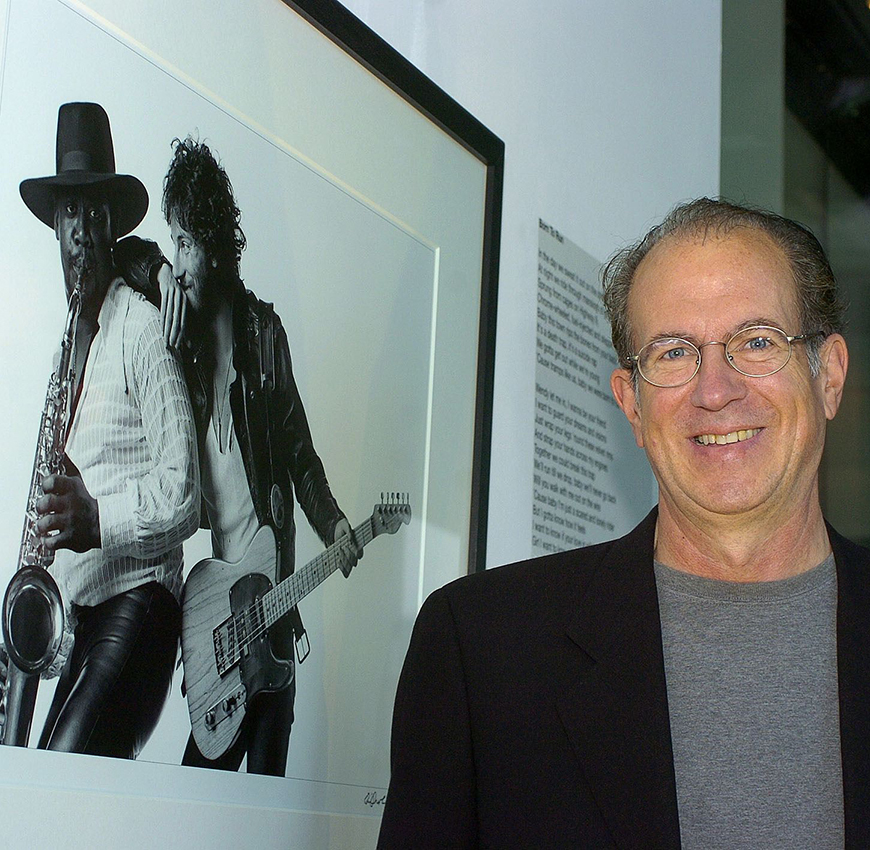

Eric Meola photographed at the 2006 opening of his Born to Run

exhibition at Snap Galleries, with his iconic cover photograph.

The Born To Run Sessions

Eric Meola sets the scene on one of the most important photo shoots in rock ‘n’ roll history.

“Around 10 or 11am on June 20th, 1975, Bruce and Clarence walked into my studio on the fourth floor at 134 Fifth Avenue, carrying their instruments and a few changes of clothing. I had the Rolling Stones album December’s Children playing.

The strobe lights were set up. It was just us – no stylist, no ‘hair and makeup’, no assistant.

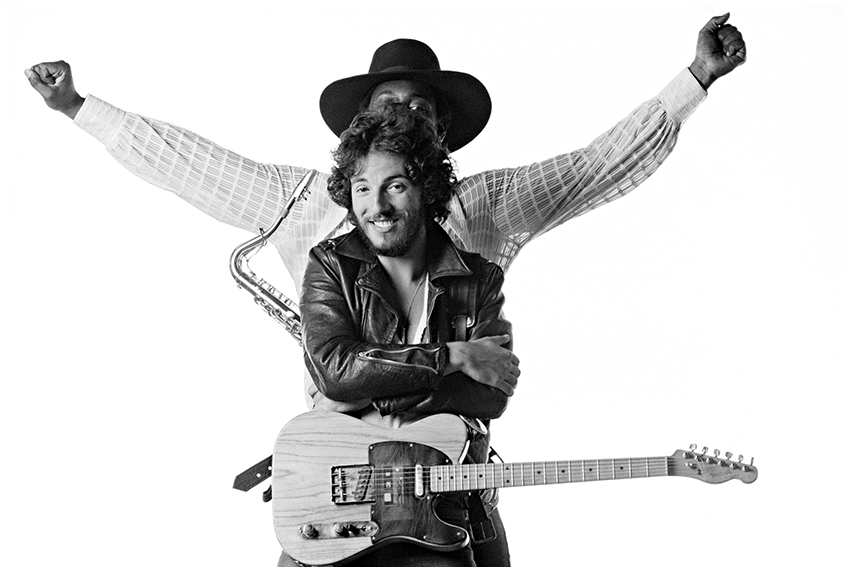

There was a six to seven inch difference in their height, and Clarence wore a tall black fedora during much of the shoot. I kept several wooden boxes around the studio to adjust for height discrepancies, though for much of the shooting I did not use them. As Clarence riffed on several sequences of notes, I began shooting.

We made quick changes of clothing and in the space of an hour and a half I shot almost 600 images. Then, we went outside, and I shot another few rolls underneath the fire escape. As we walked back to the studio, I glanced at my watch. It had been just two hours.”

A carefully curated selection of Eric’s photographs are available to purchase as signed limited editions in a choice of sizes.

You will be able to view the whole collection as you scroll down the page.

Typically, Eric offers his photographs in a choice of two physical sizes, with a maximum of 30 worldwide across those sizes.

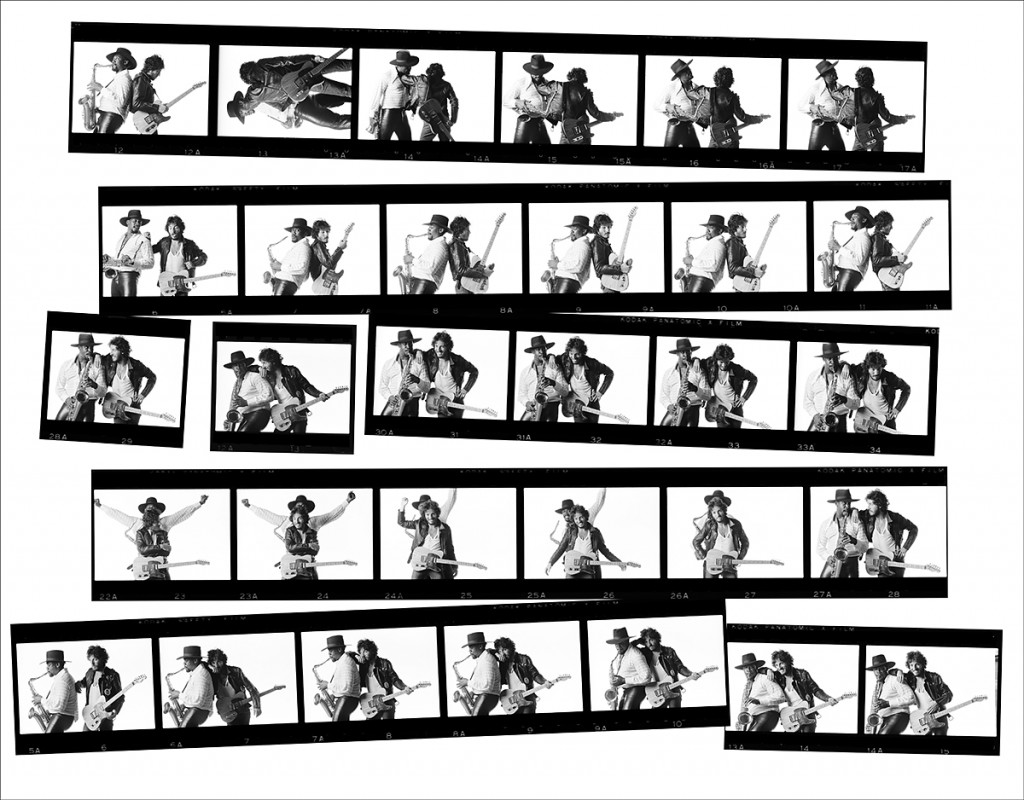

The Born To Run Contact Sheet

When Columbia Records art director John Berg was asked to show his lifetime body of work at the prestigious Guild Hall in East Hampton, NY, Eric made a contact sheet for him, which shows 31 frames from among two of the nineteen rolls he shot on that June day. Many of these frames are not in either of Eric’s Born To Run books and have never been offered as individual prints. Interestingly, you get to see individual frame numbers and entire uncropped images – and the classic Born To Run cover image is included in the third row.

Contact sheets like this don’t work in small sizes, because the individual images need to be a certain size before you can appreciate the detail. As a result this limited edition is only available in two large physical sizes. The smaller of the two has an image area measuring a very generous 20 x 25 inches (51 x 64 cm), in an edition of 25 in this size, while the larger version has an image area measuring a huge 36 x 45 inches (91 x 114 cm) in an edition of 15. To give you some perspective on the scale of the bigger version, each individual frame measures 4 x 6 inches. On the smaller version, each frame is approximately 2.25 x 3.4 inches.

Born to Run Contact Sheet

Eric continues: “Part of the cover design for Born to Run was the result of a decision that Bruce made with regard to his second album The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle.

It was released on September 11, 1973, a few days before his 24th birthday. A sprawling tone poem that echoes Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, it is one of his most romantic albums, and it moves Springsteen’s world back and forth from the New Jersey shore to New York’s streets, in songs as varied as “4th of July, Asbury Park,” and “Incident on 57th Street.” Yet for the small group of fans that was beginning to form, and who were captivated by Bruce’s every word, it contained a glaring omission—none of the lyrics were reproduced on the album’s jacket as they were on his first album Greetings from Asbury Park.

In contrast, one thing was certain about the album design for Born to Run—the lyrics would be included, as this was a set of words that Bruce had labored over for more than a year. As well, to the credit of Columbia and Bruce, nearly every single person who had any major part in the album’s creation was given credit on the album’s jacket. This included departing band members who were on some of the tracks, along with the new band members, and session musicians such as the Brecker brothers, Dave Sanborn and Wayne Andre, Springsteen’s manager and producers (Appel and Jon Landau), art directors John Berg and Andy Engel, and myself, among others. The need to include the lyrics and a lot of credits was something foremost in my mind when I chose to shoot against a white background.

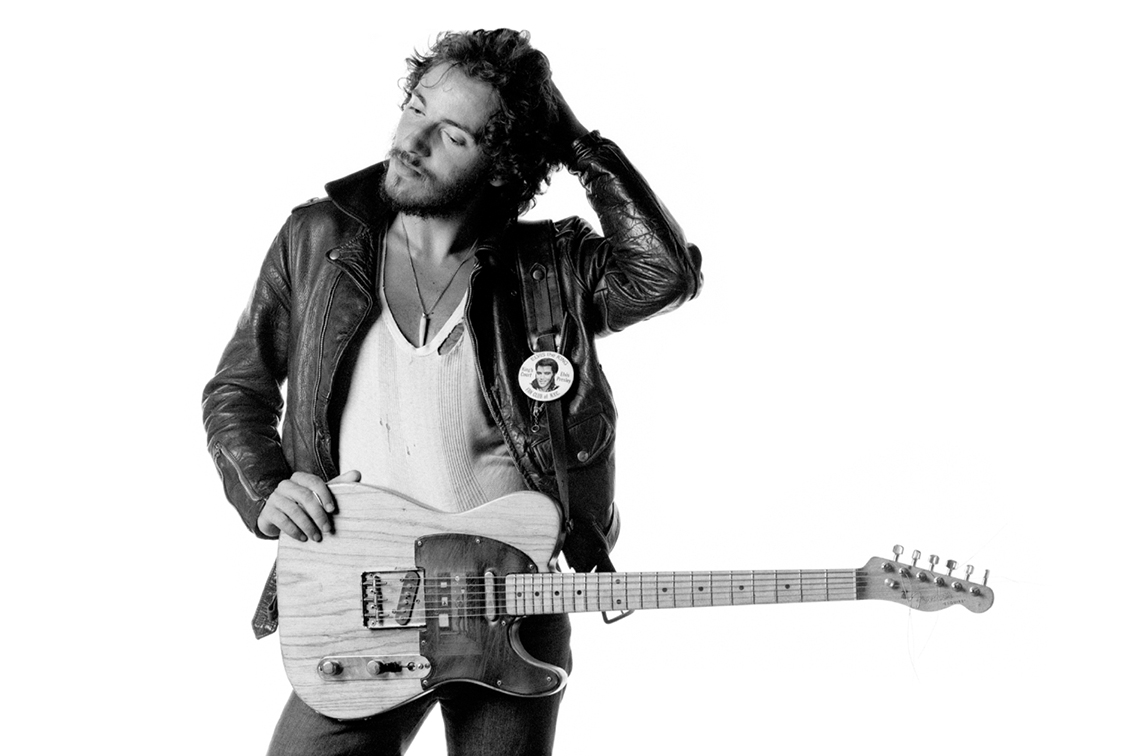

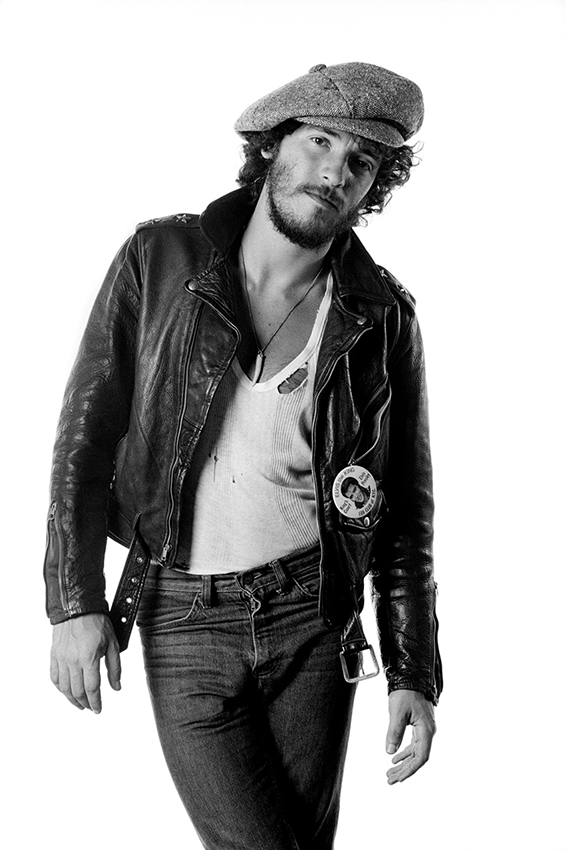

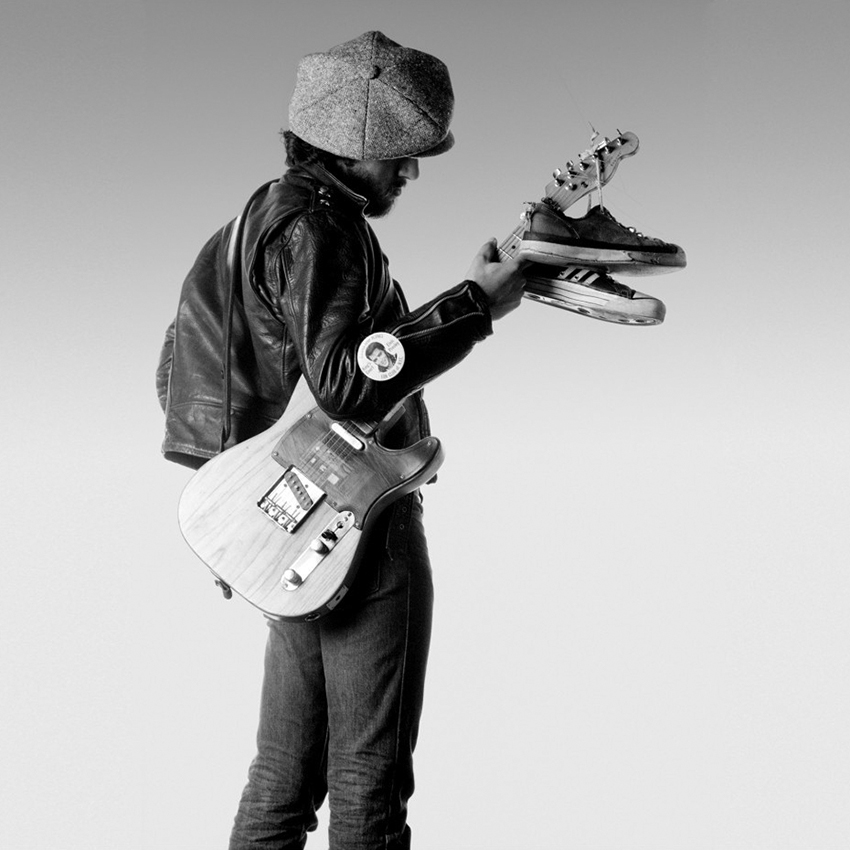

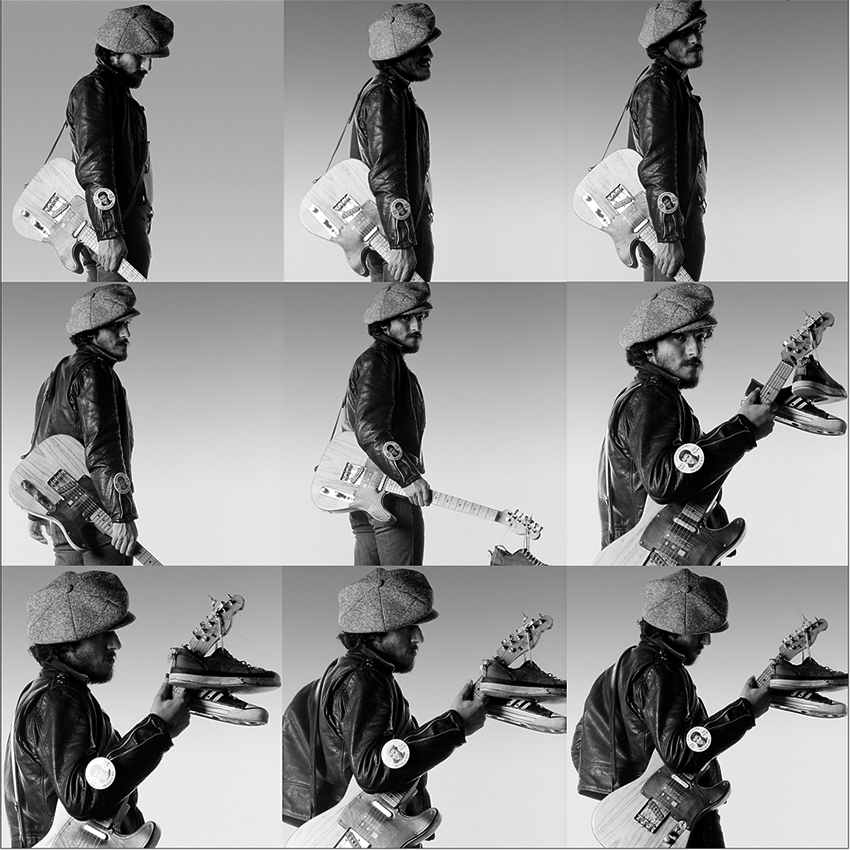

Bruce had prepared for the shoot, and brought along his ripped T-shirt and various props and talismans—an Elvis button, a pair of sneakers, his then-signature newsboy cap, and a radio. The black leather jacket he is wearing in the photograph was given to him by Mike Appel. I had also prepared, going so far as to scout an outdoor setting—a fire escape on the corner of Sixth Avenue near my studio—as I wanted to give John Berg as many alternates as possible.”

“I did not have an assistant and because I processed the film immediately after the shoot, the sequence in which the rolls were shot has been lost.

However, the sequence within each roll still remains. This shows that the interaction between Bruce and Clarence which resulted in the cover image lasted for about half a roll, or 18 frames.

Of these, there are only two where his face is turned to Clarence, and he is grinning in only one of them. Clearly, it was an instinctual moment, and one which was brought on as much by practicality, as intent. Standing on a box, he was suddenly several inches taller; Clarence’s crouch hides this and makes the height difference disappear.

After I shot a number of images in which they stood back to back, and a few in which Bruce leaned on Clarence’s shoulder while looking out at the camera, he turned to the side and looked beatifically straight at Clarence for three or four seconds as I shot two frames. Other than his standing on a box, there was no ‘setup’ for this, no premeditation – and, his guitar was not plugged in.

We were shooting fast, and if Bruce was after a particular image, he placed a lot of faith in me that in those few brief seconds I had captured the one that became famous. It happened as much because of the moment, as whatever chord progression Clarence was playing that caught Bruce’s attention.”

Eric continues: “Springsteen biographers and hagiographers as diverse as Dave Marsh and Louis P. Masur have made much of that moment and proclaimed that the cover signals an epic journey, even comparing it to Huck and Jim in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis in The Defiant Ones.

The mysteries of the Born to Run cover have assumed a mythical status that did not, of course, exist at the moment the album first appeared. The initial misspelling of Jon Landau’s name, the alternate cover with its sepia blacks and jagged type, the mystery of where Bruce obtained a membership-only Elvis button, and the herculean effort on Bruce’s part in the studio have long since magnified a sense that every last aspect of the album and its design were planned from the very beginning. My photograph of him on the album jacket, leaning on Clarence Clemons’ shoulder, would forever become part of the vernacular of American pop culture, and over the years the pose was imitated by other recording artists, including Sesame Street’s “Muppets” and NPR’s “Car Talk” hosts Tom and Ray Magliozzi.”

“When I delivered a large stack of prints and contacts to John Berg, I did not envision what he saw instantly. In Berg’s eyes, the most important part of the image was the space between their two faces, because it provided the perfect place to split the image.

Folded open so that both the front and back show, Clarence becomes the center of a riveting line of body movement along with the line-of-sight of Bruce’s magnetic gaze. Clarence was right, when he said in his quasi-biography Big Man, that he is on the back; but for Berg he provided the link to the album’s front. Berg then extended the white space to the left to accommodate the long list of credits. In its original incarnation, as 288 square inches of area, it is as much a greeting card as an announcement, as much a billboard as an album cover.

Is it, as so many writers have stated, a declaration of the friendship and camaraderie between the two men? Yes.

Was it a deliberate, premeditated statement by Bruce about race relations? Probably not.

Yet it became that, and by including Clarence from the beginning, Bruce chose not only the one remaining band member he most identified with, but the one who happened to be black. In an album of saxophone solos, from ‘Thunder Road’ to ‘Jungleland,’ it seems an obvious choice. And, a brilliant one which came to symbolize far more than any of us could have envisioned.”

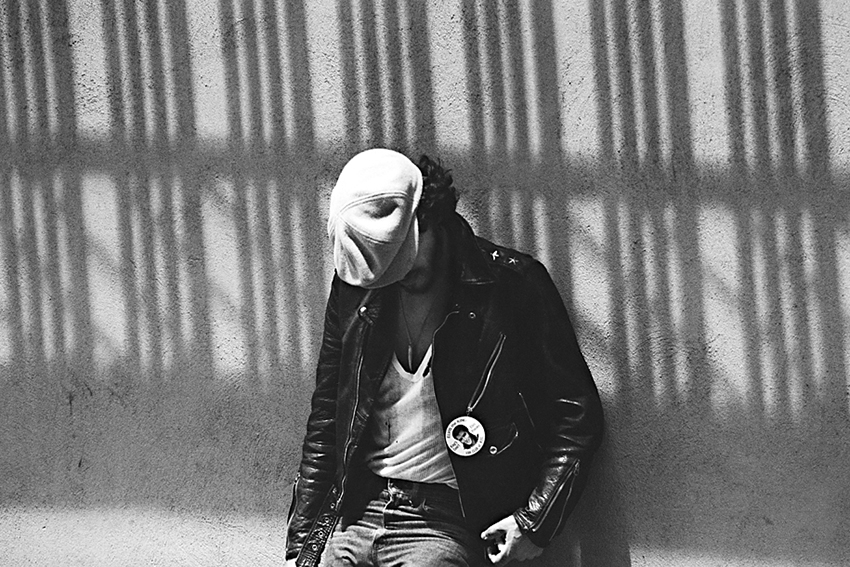

Most of the Born to Run session took place against the seamless white background of Eric’s studio set.

However he had also scouted an outdoor setting – a fire escape on the corner of Sixth Avenue near his studio, as he wanted to give Columbia’s art director, John Berg, as many alternatives as possible for the final cover design.

Outside, he created a series of photographs where the patterns from the ladders in the sunshine provided a stark contrast with the white studio backdrop.

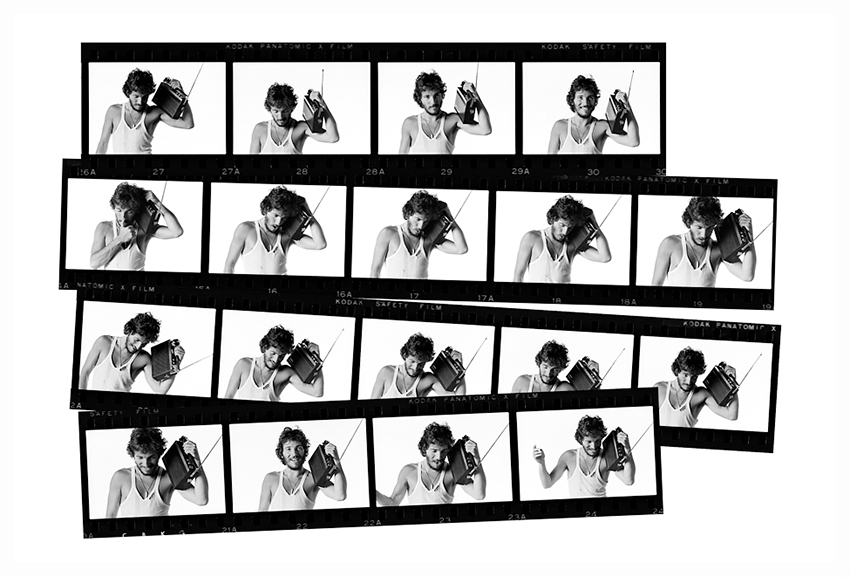

“Bruce and Clarence walked into my studio that morning, exhausted from marathon around-the-clock recording sessions at The Record Plant studios in New York. The number of frames where they are yawning attests to that.

Bruce had put some very serious thought and preparation into those two hours. Yet as he took his hat and jacket off and held the radio to his ear, and as I moved from close-ups to full torso shots of the two of them, the operative word of the day was “shoot.” Shoot lots of variations, change poses, try different things.

When he finally heard the mastered version of Born to Run, Springsteen’s reaction was that it was “The worst piece of garbage I’d ever heard.” Eventually, he came to embrace it the way we all did.

And the cover? At one point Bruce stood on a four inch tall box, back-to-back with Clarence. Then, he leaned on Clarence and looked soulfully at the man with the golden horn.

If it was a pose, he held it for a few brief seconds and two frames, and at the time I think Clarence, Bruce and I realized instinctively that there was something magical about that moment.

So would much of the rest of the world.”

Born to Run Revisited. The limited edition book from Ormond Yard Press.

Ormond Yard Press: Bringing you the bigger picture.

Born To Run Revisited, with photographs by Eric Meola, is the inaugural publication from Ormond Yard Press. It is the first in a series of large format limited edition volumes which will focus on key moments in the history of popular culture, and give them the epic treatment they deserve.

Born To Run Revisited is a book on a spectacular scale: a hardcover volume housed in its own printed slipcase and measuring 24 inches high x 18 inches wide (60x45cm) when closed, 24 x 36 inches (60 x 90cm) when open, with 96 pages of photographs, and an introductory essay by Eric Meola.

The physical scale may be large, but the edition size is reassuringly small – just 500 individually signed and numbered copies are available to collectors worldwide.

Born to Run Revisited is available now

Interlude – Meeting Bruce Springsteen

“As a professional photographer, I always consider myself as a hired gun. Although I love Bruce’s music, and the lyrics to his songs, I have a job to do, and my passion is tempered by the need for my images to tell a story” Eric Meola

So how did Eric Meola come to meet, befriend and then photograph Bruce Springsteen ? Over to Eric…

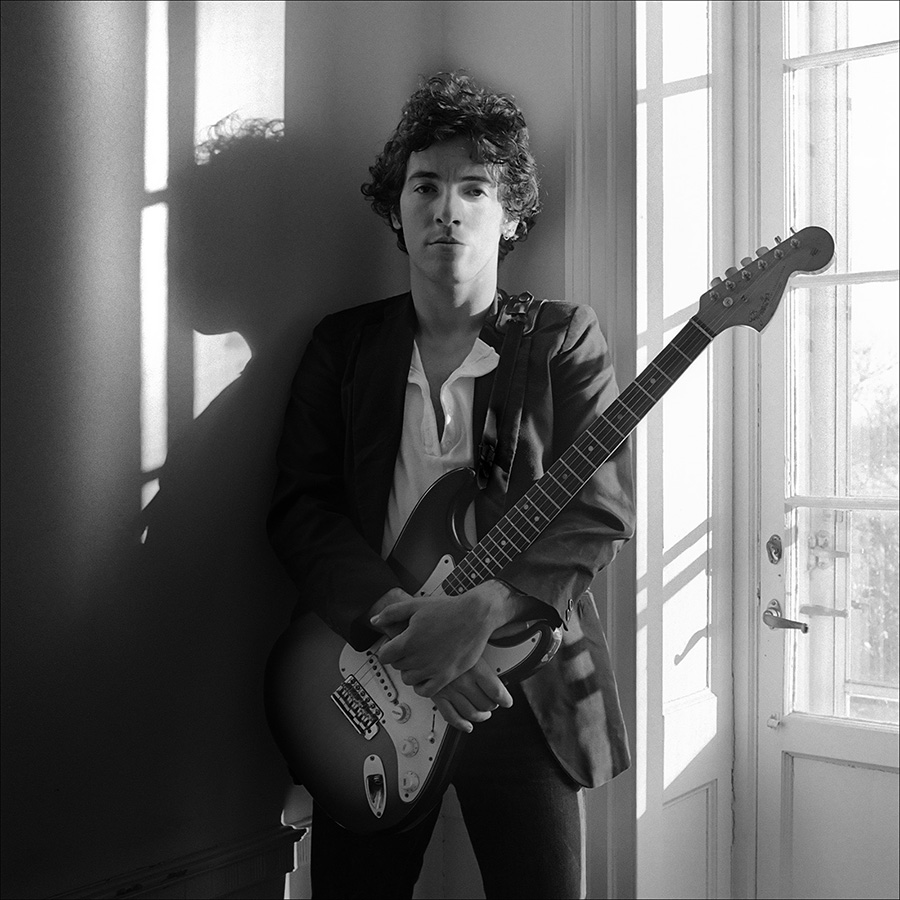

“As an aspiring photographer, I lived in New York in the early Seventies, around the corner from a nightclub called Max’s Kansas City. Then, one night in 1973, I had the serendipity of going to see someone by the name of Bruce Springsteen perform there. He sang what I thought then was a god-awful song with the title “Mary Queen of Arkansas,” and several brilliant ones, such as “It’s So Hard to Be a Saint in the City. That was it. From that moment on, I was hooked.

On Saturday, August 3rd, 1974, I was standing near the corner of Fifth Avenue and Central Park South in New York, when it began to rain. I ran under the overhang of the Plaza Hotel and came face-to-face with Bruce Springsteen, who was about to do a concert in Central Park. All I can remember is that I got up the nerve to introduce myself and ask about some of the words on Bruce’s album The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle. Unlike Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., and every Springsteen album since then, there were no lyrics on the jacket sleeve.

Eleven days later, I rented a car and drove down to Red Bank, New Jersey, where Bruce was playing at the Carlton Theater. Mike Appel, Bruce’s manager at the time, was standing out front, wearing a marine drill sergeant’s hat, and, noticing the camera slung over my shoulder, stopped me. I bluffed my way in, saying I was taking pictures for Time magazine. After the show I saw Bruce in his dressing room and while we were talking he suddenly waved his arm in an arc behind him and invited me down to the Jersey shore. In that simple gesture the imaginary world he had painted in his first album, a misty paradise by the sea, came alive. In less than a year, the “Born to Run” tour would begin in Providence, Rhode Island; less than a year earlier, I had walked around the corner from my apartment to see Bruce perform at Max’s Kansas City.

In the spring of 1975, I took a subway one day to Penn Station, bought a train ticket, and headed south to Long Branch, New Jersey. A little over an hour later, I walked out into the sun and, after asking a few questions, found my way to West End Court, and a small cottage with the number 7 1/2 on it.

Now, as my hand approached his front door in slow motion, I got up the nerve to make a “rat-a-tat-tat” knock on the door. Silence, total silence. Nerd that I was, I looked at the glowing red numerals on my Pulsar digital watch, and knocked again. Knowing something must be amiss, I walked around the corner, to a small, old-fashioned pharmacy, and dialed Springsteen’s number from a pay phone. Nothing. I let it ring. And ring. After several trips back to the front porch, and one more call, the door finally opened. Forty-five minutes later, I was sitting next to Bruce in his flame-painted, yellow ’57 Chevy, cruising with the top down on one of many roads immortalized in his songs, Highway 9. I had a camera pressed against my right eye, and I was shooting frame after frame as Bruce drove. One moment in particular froze in my mind, as he turned and looked at me, with his hair blowing in the wind, and just grinned.

You can see it right here.

Just three months later, Bruce would be on the covers of Newsweek and Time in the same week, and my photograph of him leaning on Clarence Clemons’ shoulder would forever become part of the vernacular of American pop culture, as the cover of Born to Run was imitated by everyone from Sesame Street’s “Muppets,” to NPR’s “Car Talk.

My own fledgling career as a photographer was beginning to show promise; I got an assignment to photograph coffee plantations around the world, and spent the next couple of months shooting in Kenya, Columbia, Mexico and Guatemala. Rumor had it that Bruce was enjoined from going into a recording studio, and suddenly it seemed that Bruce was fading from view as quickly as the press catapulted him into the stratosphere.”

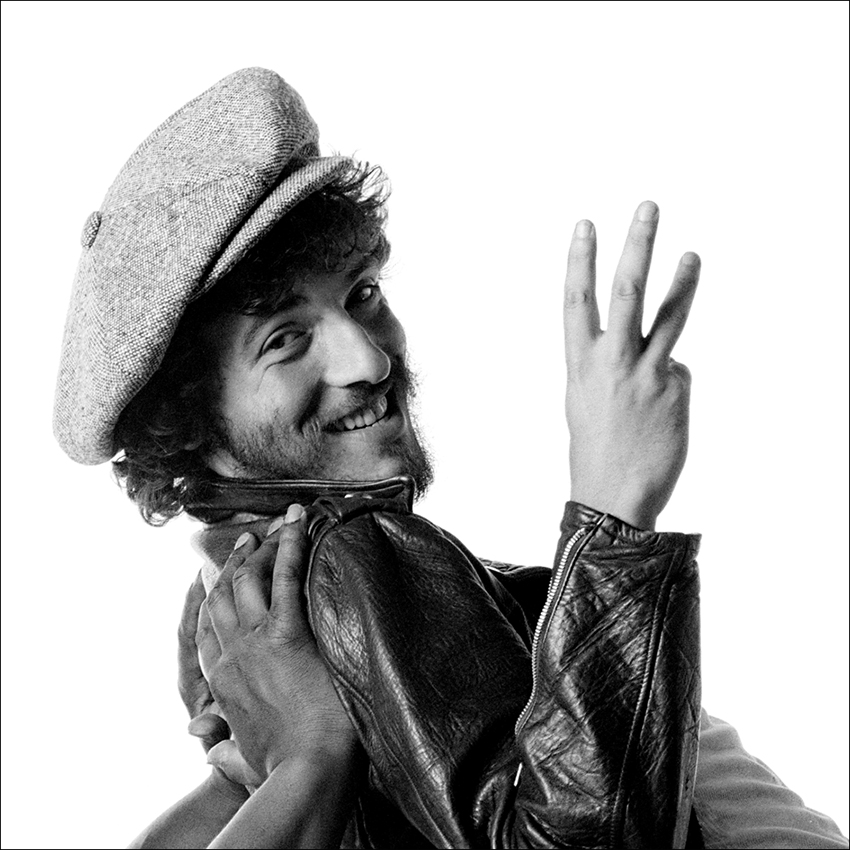

Finishing Born to Run (The Record Plant)

Eric Meola shares the story behind this little known close up portrait.

“During the last month of recording the album Born to Run, Bruce would spend nearly every waking hour at the Record Plant on West 44th Street in New York. The last week of finalizing the album was particularly intense, and given the mood I knew not to interfere.

This image was made a few days before Bruce finished the album. I showed up and waited in the lobby of the building, and finally left to go home. Bruce suddenly appeared and we talked briefly – he was amused by the custom made T-shirt I was wearing which had the words”BORN FOR FUN” emblazoned on the front in red, white and blue.

In the hot July sunlight, I got a few portraits of him grinning before he went back in to work some more on the song “Jungleland”. In a few days the album would be finished.”

Limited editions of this photograph are available at a very special price.

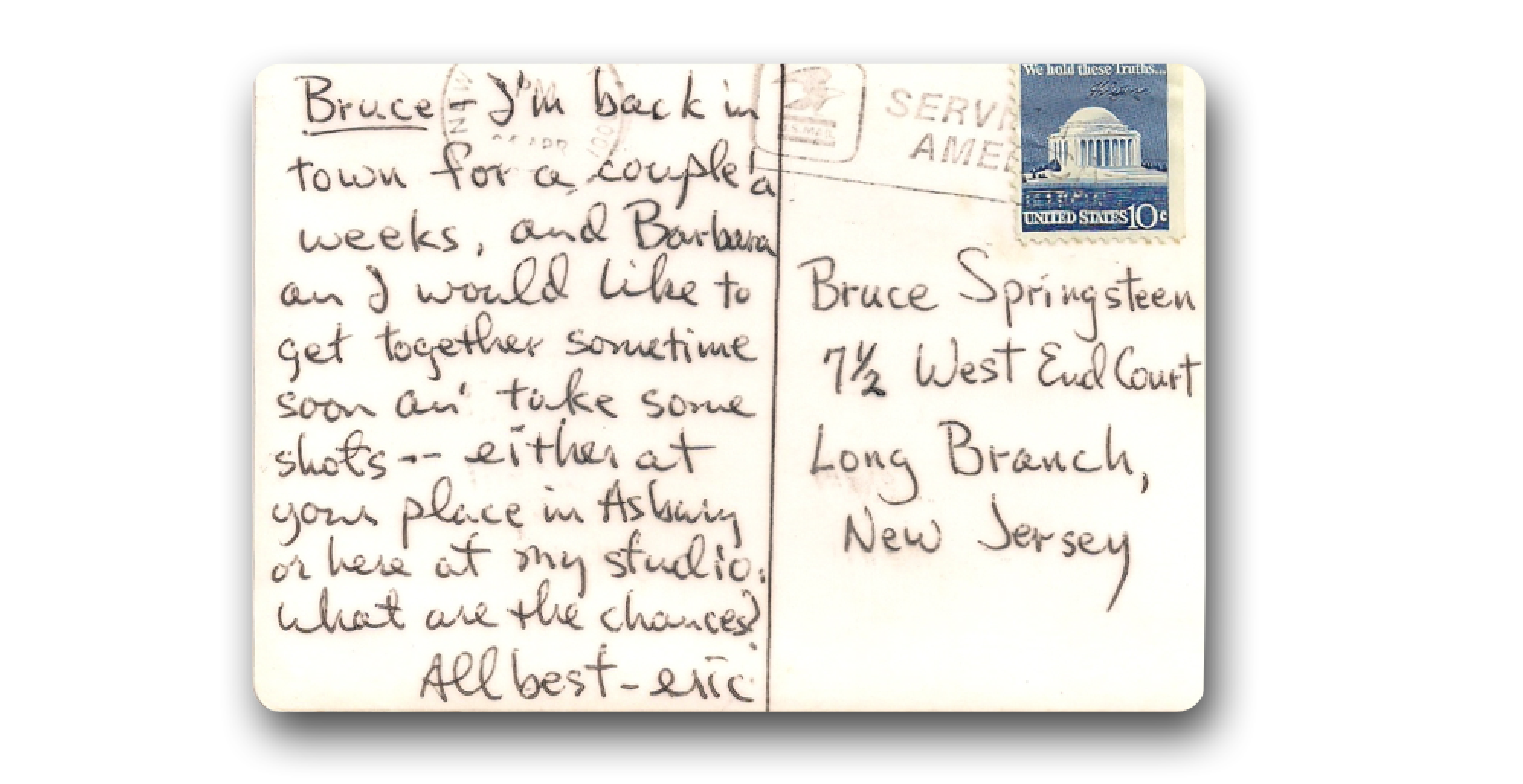

Postcard written by Eric Meola to Bruce Springsteen in April 1975

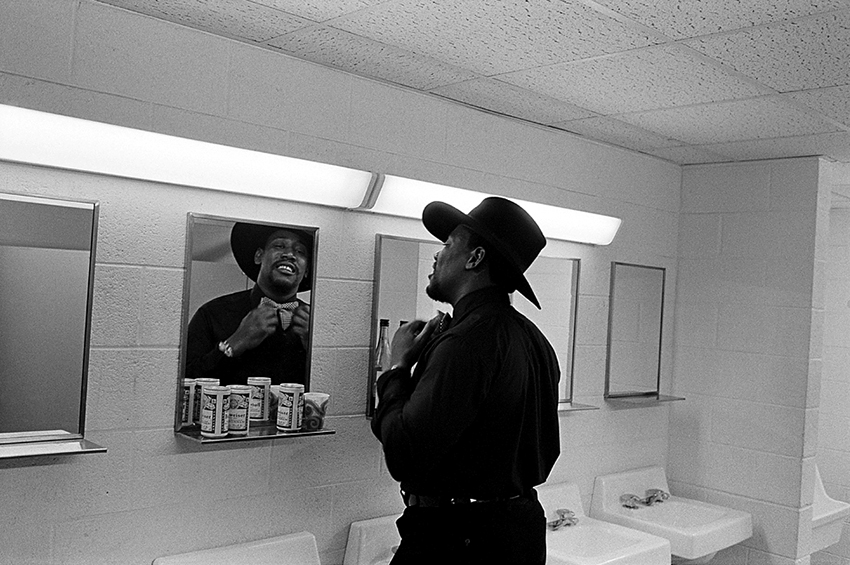

Darkness On The Edge Of Town Sessions

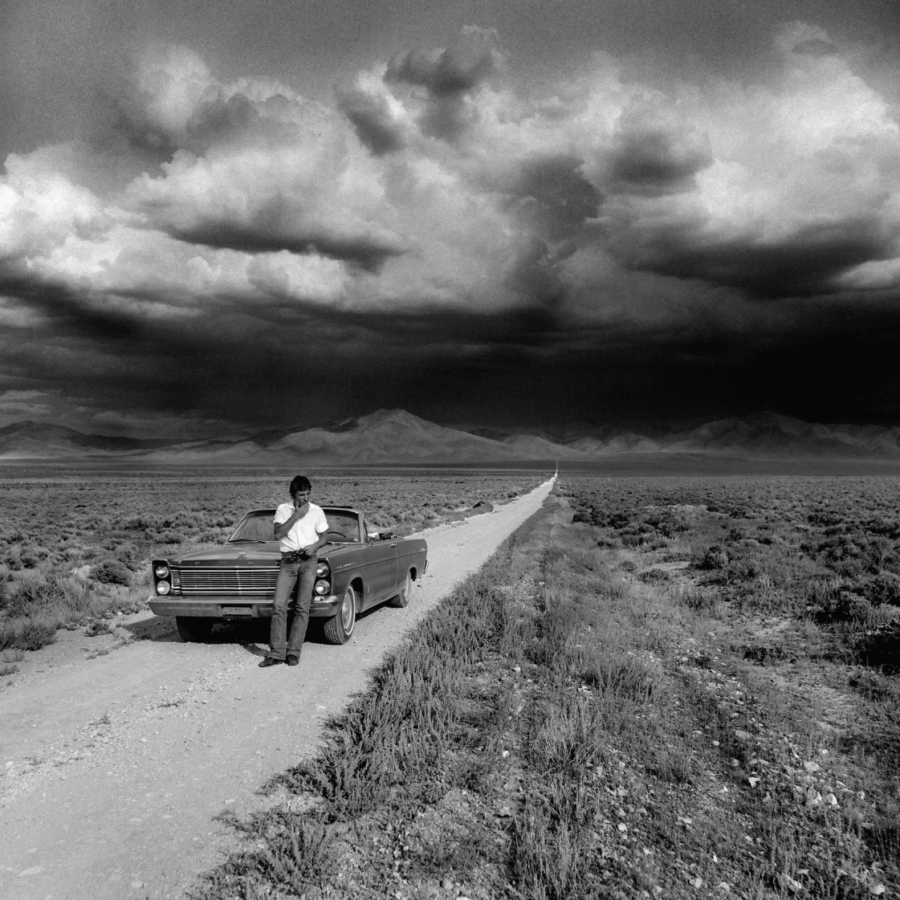

Visitors to Eric Meola’s first ever gallery exhibition of photographs from his Bruce Springsteen archive at Snap Galleries in 2006 will have been treated to the sight of this beautiful photograph from 1977, titled “Darkness” by Eric. A handful of lucky people got to be the proud owners of the large format 30 x 30 inch limited edition sepia toned dye transfer photograph that Eric offered to collectors during the exhibition.

The question everyone asked was, of course, “Is that really Bruce?” The answer was of course “Yes” and the subsequent publication of Eric’s book Streets of Fire in 2012 provided an emphatic answer. The second questions everyone asked was “What colour was the Galaxie 500?” It was red.

Bruce Springsteen fans will of course be familiar with the Live 1975-85 box set. What you might not know is that “Darkness” here was in the running as a cover for that box. Columbia’s art department ran some mock-ups, printing the image 14×14 inches and overlaying the titles Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band: Live 1975-85 across the centre. Some of those test prints are in the hands of Springsteen collectors, but the real deal very much remains the original large format “Darkness” photograph offered by Eric in 2006, with an image measuring 30 x 30 inches, and of course, no writing overlaid.

It is a grand sweeping photograph, with drama in the mountains and skies, and the car seeming to flash white light from its position dead centre of the vanishing point.As Eric recalls: “One afternoon, on a long dirt road off Highway 80, I asked Bruce to drive straight at the camera as ominous clouds from a late summer storm began to form overhead.” It conjures up memories of Bruce’s lyrics from “The Promised Land.”

Eric picks up the story: “In mid-June 1977, I got a call from Peter Philbin, an A&R executive at Columbia Records, and we drove down to central New Jersey to see the “E Street Kings” play a game of softball.

Someone casually whispered that the Mike Appel lawsuit had been resolved just a few weeks earlier. I realized then and there that whatever the settlement was, Bruce would soon be back in the studio, and recording songs for a new album.

A few weeks later, I drove my girlfriend’s ’52 Mercedes 170S—a car that would have been at home in Orson Welles’ The Third Man—down the Jersey interstate; “Baron,” her Russian wolfhound-German shepherd mix, bolted from the car as I walked up to the farmhouse door and knocked. It was time to make some more photographs.

During that summer and into the fall, Bruce was holed up at the Navarro Hotel on Central Park South. I had been lucky with the cover shot for Born to Run. Lucky in terms of being at the right place at the right time. Yes, I had nailed it, but now there was a new album, and the sense that Bruce had to prove it again was palpable. I had trouble adjusting to this new Springsteen—the beard was gone, and along with it, most references to the Jersey shore. Six years before Darlington County would rivet the center of a song by that title on 1984’s Born in the U.S.A., it appeared in the 1978 song “The Promise.” After the grandiose, operatic Born to Run, I sensed it was time for bringing it all back home. But where was “home?”

When Bruce and I got together to discuss ideas, I brought along three books. One was Robert Frank’s The Americans. Two others were David Plowden’s Commonplace, and also Desert and Plain, the Mountains and the River. Although I knew that Bruce would be drawn to Frank’s book, Plowden’s work is an acquired taste for most people, yet it resonated with me at the time, and the imagery is, in retrospect, echoed in much of Bruce’s lyrics. The very title Commonplace speaks to “My Hometown.” The photographs of barns, gas stations, fields, doorways, churches and interiors, in places like Red Cloud, Nebraska, are the kinds of places we pass by every day, yet seldom notice.

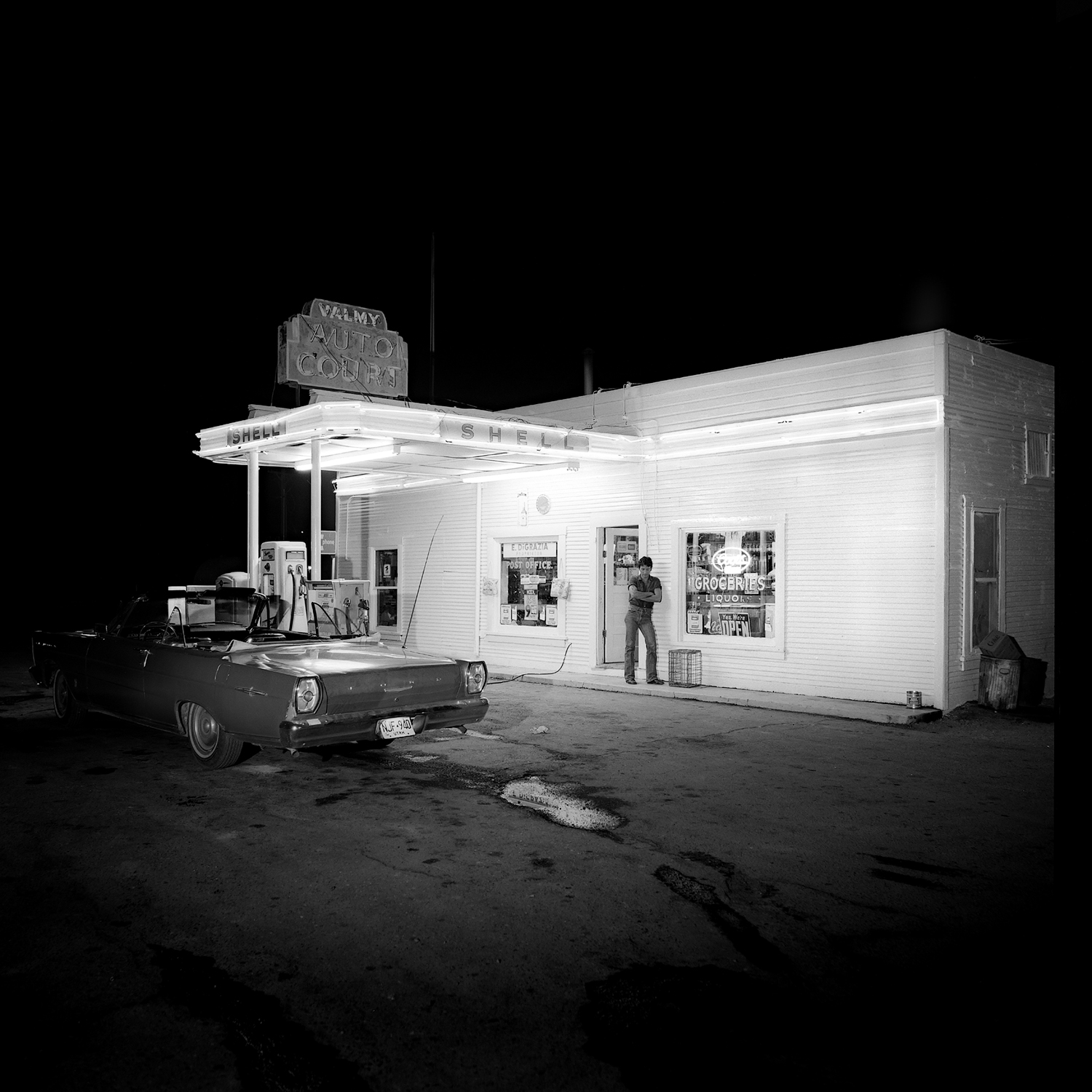

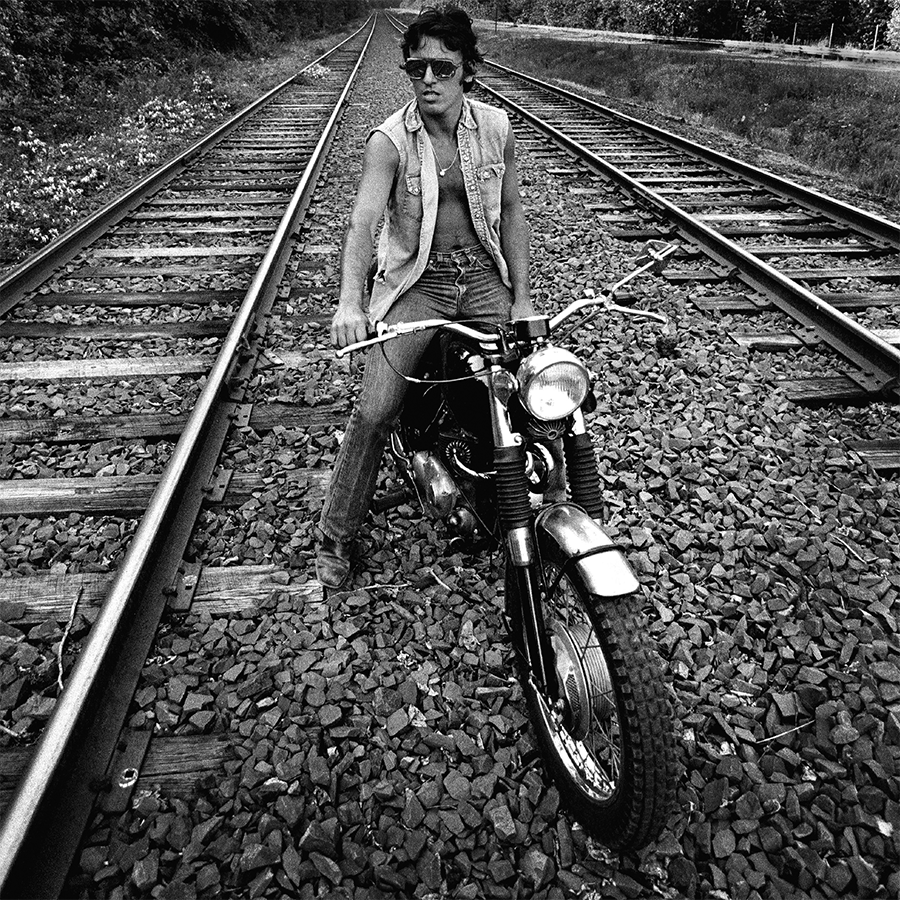

“In the fall of 1977, I spent days looking at maps, and then settled on a stretch of Route 80 between Salt Lake City, Utah and Reno, Nevada.

Finally, the plans came together—we would fly out to Salt Lake City, find an old car, and drive it across the desert to Reno. Then, the day before we were due to leave, Elvis died. Just before we headed west, Bruce got his first credit card. At the time, young mister Springsteen certainly didn’t have a long history of credit worthiness. After all, the band was living on everything borrowed—borrowed time and borrowed money. I think Bruce’s lawyer had arranged to get a credit card for Bruce in the unlikely event we would become stranded somewhere west of the Mississippi.

Now, this wasn’t the Lewis and Clark expedition, but who knew what dangers lurked in the vast unknown expanses of the promised land? We certainly didn’t want to make it through the Donner Pass, with the hypnotic aroma of an all-American cheeseburger wafting just out of reach, only to have our credit run dry at Brenda’s Café.

I remember how bemused Bruce was with that thin, plastic card, the gold sheen gleaming in the sun, as he waved it in the air, and sardonically announced “the ‘world of respect,’ yes sir, the ‘world of respect.’” Bruce polished off the delivery with his trademark double-shot ‘heh heh,’ and then he bent over and broke up in a paroxysm of laughter, the tears running down his face, as he reveled in his newfound key to the universe.”

“We flew to Salt Lake City on schedule, and spent an afternoon in used car lots, finally settling on a red convertible—a 1965 Ford Galaxie 500XL with bucket seats.

In my mind, I was already visually closer to what would be the album Nebraska than I was to “Darkness.” I was focused on the landscapes and, to a lesser extent, Bruce. That vision would have to wait for David Michael Kennedy’s stark, chilling, almost anonymous photograph through a car windshield.

The conversation during our drive across the desert was mainly about the “Memphis Mafia,” and Elvis. Then, something happened that was…well, almost biblical. We had come to a place marked on the map as Unionville, just to the west of Battle Mountain. Nearby, there was an abandoned one-room schoolhouse and a cabin where Mark Twain once lived while writing Roughing It. I took some photographs of the gravel road, and of Bruce driving towards the camera, as the sky began to darken. But Bruce was restless, so we left the road at Unionville, and grabbed a bite to eat at a nearby roadside cafe.

It was August…August 22nd. We had spent the night before in Elko, and because we had been driving all day and all night, we tried to fall asleep in the car. But on that restless night, I slept fitfully on the hood of the Galaxie, listening to dogs howling all along Main Street.

When we went back, the sky had gone black and the wind had come up. I photographed more images including a shot of Bruce in front of the car, leaning on the hood—a long, thin, dusty dirt road going off in the distance behind him, disappearing over Battle Mountain. It began to rain, and flashes of lightning filled the valley floor. It was one of those days and moments that stay with you to the grave. There was that strong, fresh, electric smell of ozone after lightning has cleared the air, and the feel of moisture mixed with dry desert wind—something I had felt only once before.”

“Bruce’s sense of drama deeply influenced the way I photographed… Where Born to Run had been shot against a white background, now everything emphasized black.” – Eric Meola

“We flew back home a few days later, and most of those landscape images were never used, like much of what I shot for Bruce during those years.

Bruce was transfixed by that storm, and by my photograph of those “dark clouds rising from the desert floor.” However, Jackson Browne had released an album in late 1977, called Running on Empty, and it featured a stylized road going off to the horizon. More importantly, Frank Stefanko’s photograph, which was used on the cover of Darkness on the Edge of Town, telegraphed a more visceral sense of what the album was about—those dark, lonely moments when “the night’s quiet, and you don’t care anymore.” One of the best afternoons of my life was spent with Frank, where he made that photograph in Haddonfield, New Jersey.

Going through my files and choosing images has been a journey of memories—afternoons in Holmdel at Telegraph Hill Road, drives on Highway 9, days in my studio, and E Street softball games. All good times, simply trying to put a visual sensibility on lyrics that have resonated with me and with most of us as we grew up over the past few decades. Bruce’s words have informed a generation and changed many of us profoundly. I hope that some of my photographs reflect who he is and what those words mean to me.”

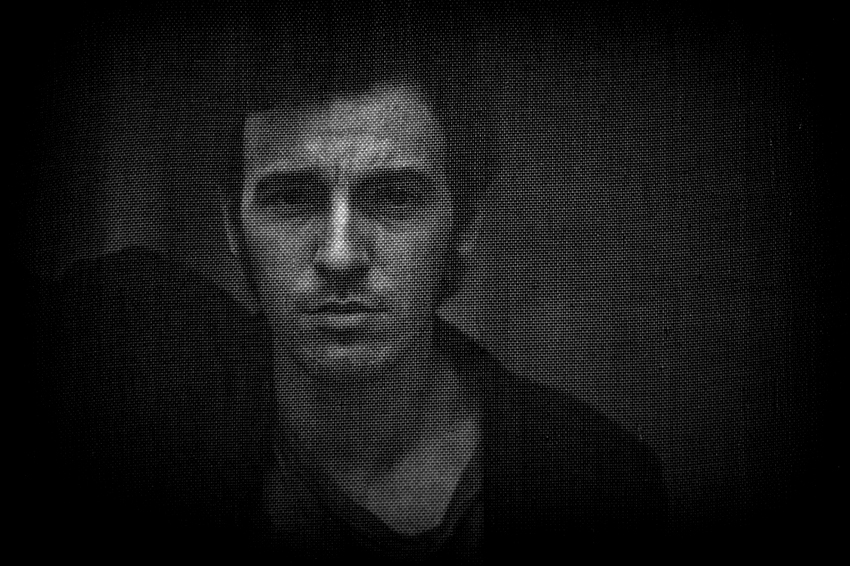

Bruce Springsteen, NYC studio, 1978

In 1978 Columbia Records and Bruce Springsteen thanked the record selling US industry via a Billboard magazine centerfold, as Darkness On The Edge Of Town sold enough copies to turn platinum late that year.

Eric recalls: “Bruce had brought a lot of different shirts to the shoot, but I liked the simplicity of the black tee. Although there was light on the dark grey background, I went for a single strobe, high and dead center overhead, with just a very slight reflector fill. I tried to think of how the image might be used, and wanted to leave plenty of room for type. I wanted no gimmicks–just a straight-on portrait of a musician whose previous album was a masterpiece, and who had been tied up in legal wrangling for nearly three years.”