Keith Morris was a highly regarded British photographer whose portfolio included Nick Drake, Marc Bolan and Elvis Costello.

In a career spanning over four decades, photographer Keith Morris had a rare, even perhaps unique ability to discover and draw out the underlying personalities of his subjects. And although best known for his iconic images of the likes of Marc Bolan, Nick Drake, and Elvis Costello, he also applied his eye to literally hundreds of other musicians, groups and indeed people from a diverse range of backgrounds, as well as the cultural and social conditions of the times he lived in.

Born in 1938 in Wandsworth, South West London, Keith was educated latterly at Farnham Grammar School where he excelled as athletics captain, at 17 coming second in the national youth 1500 metres race. Despite an aptitude for sports which he admittedly fulfilled in later life, he went on to study photography at Guildford Arts School, later gaining an apprenticeship with David Bailey at the height of the ‘swinging sixties’ and cutting his professional teeth with the burgeoning underground press, most notably Oz, International Times, the fledgling Time Out and the short-lived sex newspaper, Suck (for whom he took some infamous nude photos of Germaine Greer).

During his time at college, he undertook a series of photographs in South Wales pit villages and in the streets of ‘60s London which first revealed his talent for capturing a telling image and the human temperament that lay behind it.

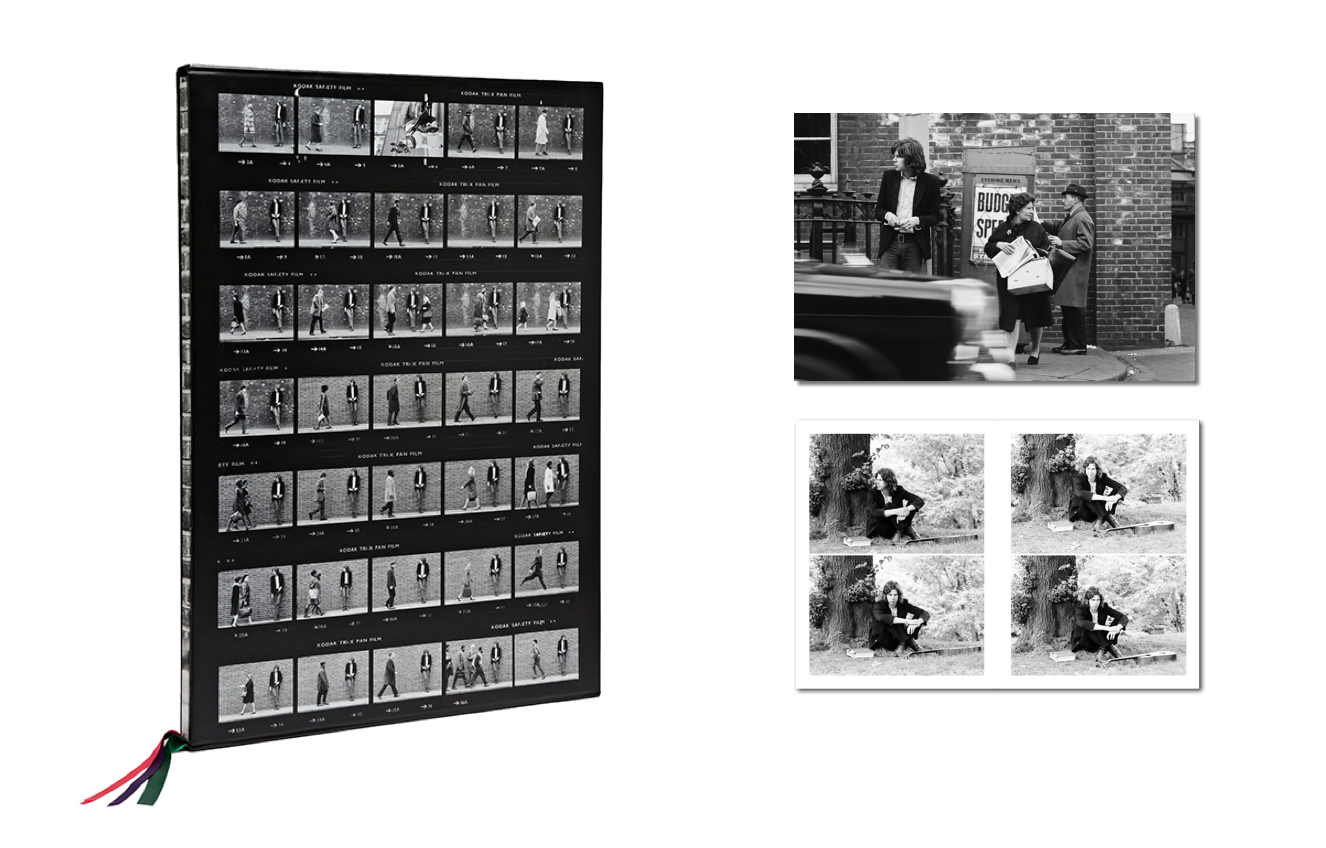

Having already worked for Joe Boyd’s Witchseason Productions, Boyd asked him to do a short session for newcomer Nick Drake’s first LP, Five Leaves Left. Taking just a few dozen shots that perfectly conveyed the artist’s shy, yet world-weary nature, he was virtually the only photographer the singer/songwriter would work with before his premature death in 1974. Keith went on to take a whole series of images of the key players in the UK folk and folk-rock scene for Island records, including Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny, Richard & Linda Thompson, Shelagh Macdonald and Martin Carthy.

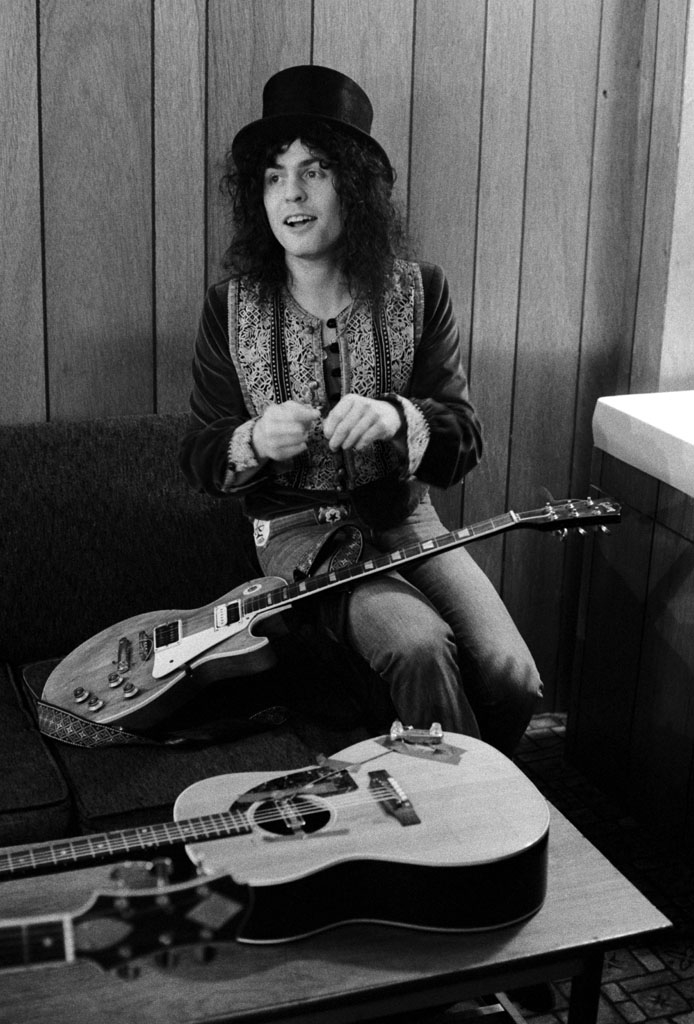

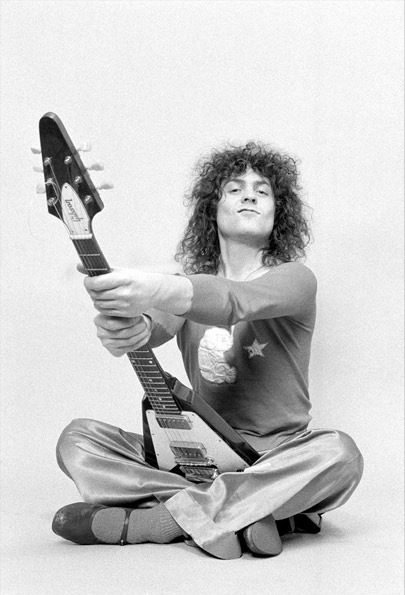

Unburdened by music trade stereotyping, he developed a similarly exclusive, if longer-lived relationship with Marc Bolan after the diminutive glam-rocker became Keith’s neighbour in Little Venice. Keith later toured extensively with him in Europe and America and became ‘house photographer’ on “Born to Boogie”, the film Bolan made with Ringo Starr and Elton John in 1972.

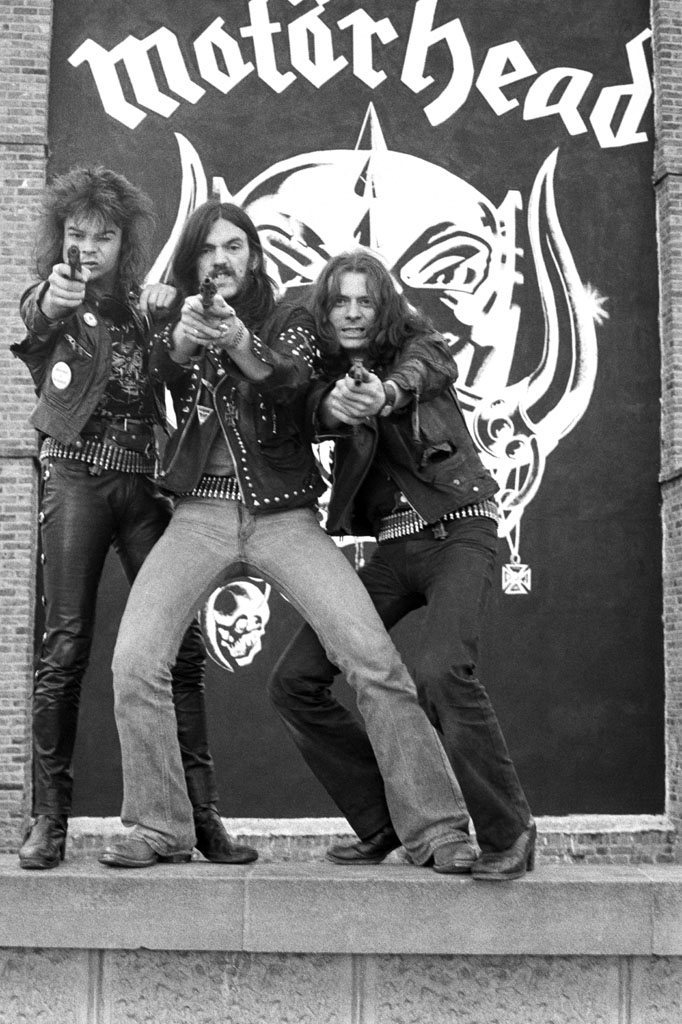

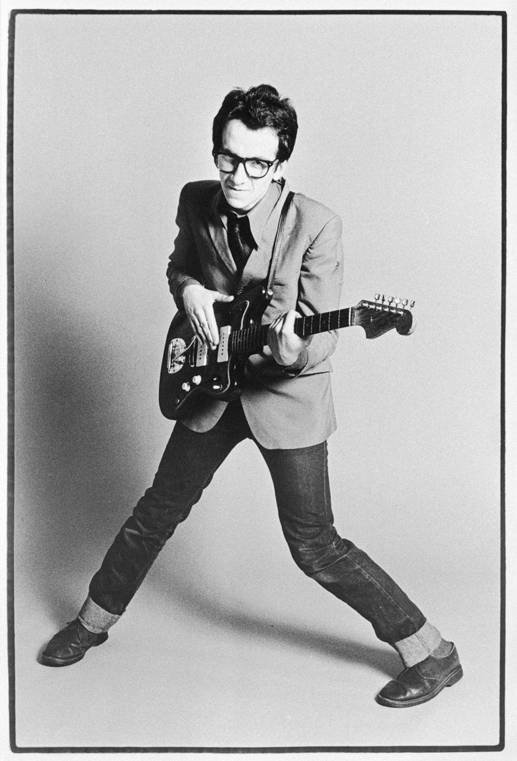

From the late ‘60s up until the early ‘80s, Keith photographed a vast number of artists both famous and less so, including The Who, Nick Lowe, Rolling Stones, Dr. Feelgood, Steeleye Span, Janis Joplin, B.B. King, The Damned, The Kinks, Eddie & The Hot-Rods, Steve Winwood, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, John Cale, Led Zeppelin, Bob Marley, John & Beverley Martin, Motorhead and of course Elvis Costello & The Attractions with whom he had a similarly extensive and intimate creative partnership as he’d had with Marc Bolan and Nick Drake.

Keith was particularly empathetic with artists who shared his no-nonsense attitude to rock’n’roll and life in general, which as well as so many of the bands he worked with, also underpinned his long-standing dealings with management and record companies such as Witchseason Productions, Island and Stiff Records. Perhaps uniquely in his chosen field, these relationships were unburdened by the prejudices of narrow genre categorisation, embracing everything from folk to punk to mainstream pop.

By the mid-‘70s Keith had already developing a passion for scuba-diving and with his typical energy and determination he quickly moved up the ranks of the British Sub-Aqua Club to become an instructor. He also took up long distance running, regularly finishing the London Marathon in under 3hrs 30mns to achieve Elite Group status well into his sixties.

However his enthusiasm for rock’n’roll remained undiminished throughout, and as ex-Stiff Record’s boss (and later Elvis Costello’s manager) Jake Riviera explained, “He had the knack of knowing exactly what a band was all about and capturing it quickly. When he came down to Canvey Island to do Dr. Feelgood’s album, Malpractice, Lee Brilleaux (their formidable lead singer) said he’d got a ‘bit of business to do’ and could only give him twenty minutes, but Keith said ‘no problem’, and it wasn’t. A bloody masterpiece, in fact.”

And that perfectly sums up Keith’s modus operandi, relying as he did on keenly honed instincts and technical prowess to catch the moment and the forge a lasting impression with the minimum of fuss. But as is too often forgotten in these days of instant digital imagery and computer fakery, the best photographers of that earlier era completed and finessed their work not with a few clicks of a mouse, but in endless hours spent in darkrooms working their voodoo with enlargers, masks, gauzes and chemicals. And in what is fast becoming a forgotten craft, Keith was undoubtedly both a master and a perfectionist.